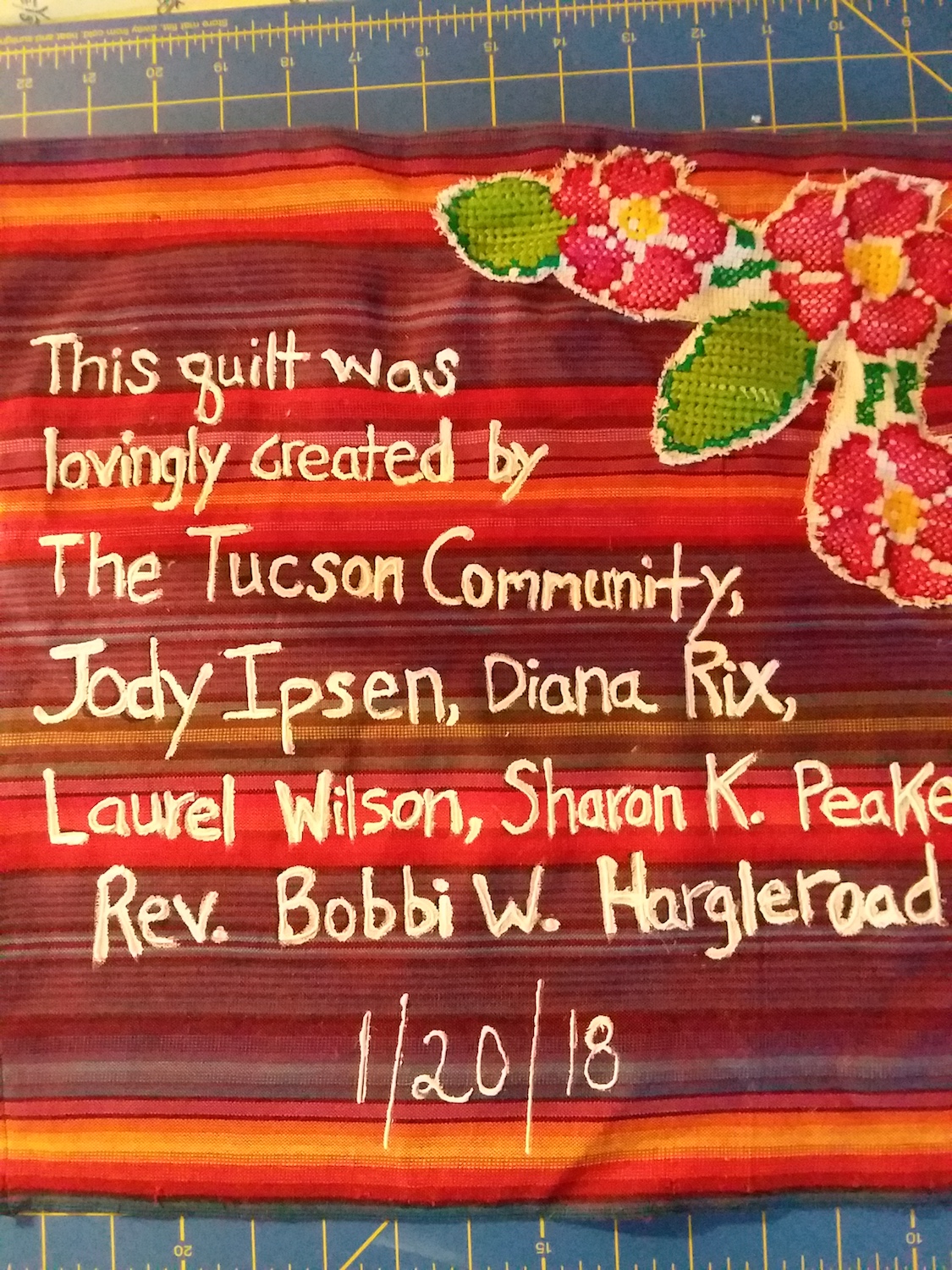

Quiltmakers’ statements:

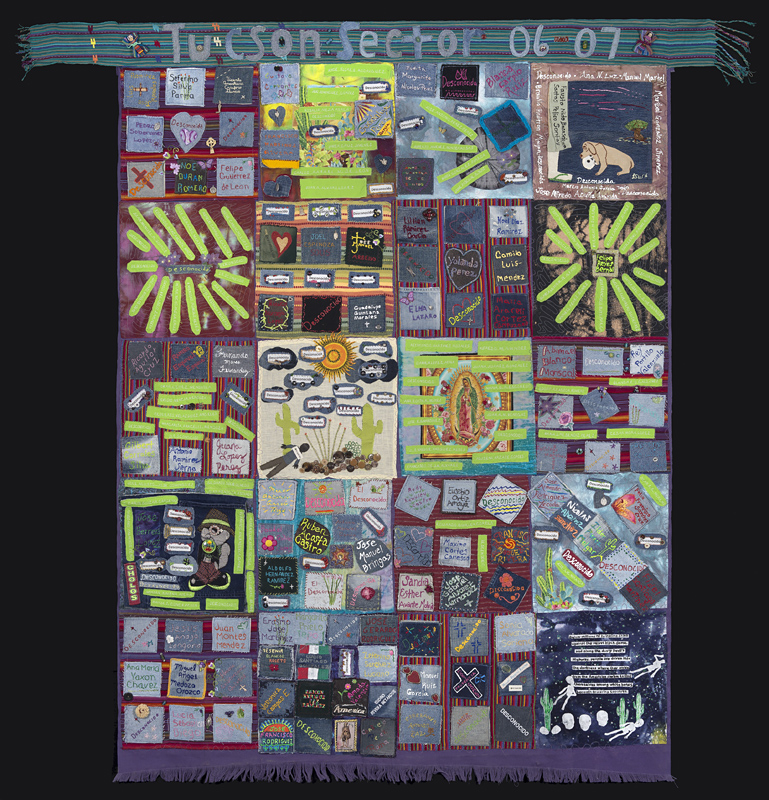

For over a decade I’ve hiked in the rugged Sonoran Desert to prevent migrants from dying of dehydration and exposure. In 2007 I decided to create the Migrant Quilt Project out of the abandoned clothing that migrants deliberately left behind. The border crossers’ personal items became the fabric for the quilts as they best represented the difficult journey they made in order to find a better life inside the United States. The clothing, often sun bleached and worn, created the backdrop in which all the quilts were made. Sometimes the quilts are embellished with rosaries, prayer cards, pesos, and milagros in order to illuminate the plight of their migration.

As I worked to prevent the deaths in the desert, I enlisted quilters and textile artists to create quilts that would highlight the border deaths. Through the alchemy of found items we drew attention to the border crossers’ stories through quilting, an American folk tradition that often speaks to human rights issues.

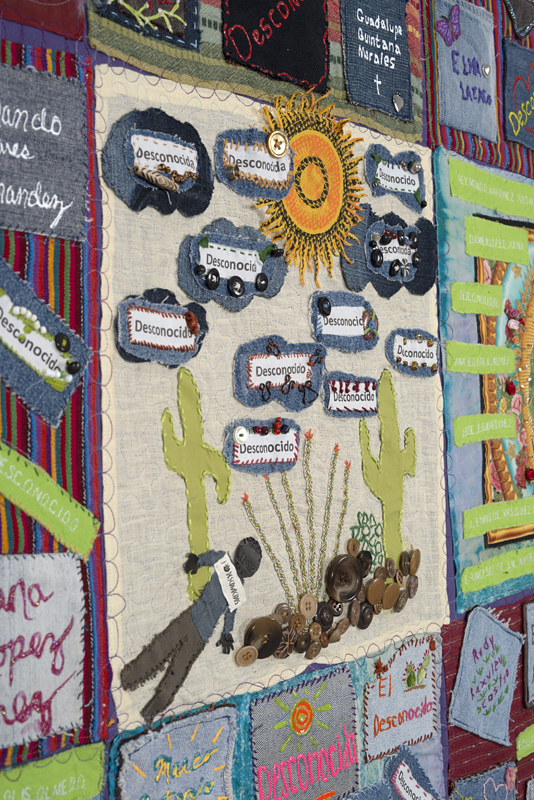

Over the course of several years, I worked on the 2006-2007 quilt with others. The names we embroidered or painted onto jeans and shirts were a rallying cry for humane immigration reform. I found the work profoundly sad yet cathartic. I decorated the quilt with dignity for the deceased so that if family members of the decedents found their loved ones’ names on it, they would know that someone created a memorial for them and that their lives and deaths were not in vain.

While the quilts carry a political message, they are first and foremost a living memorial to all those who died while pursuing the American Dream. It is my greatest hope that you find these quilts inspirational so that you may champion humane immigration reform.

Jody Ipsen

I lived out in Marana years ago near a migrant through-way. I regularly found jackets, sleeping bags, backpacks, and empty bottles of electrolytes on my land. Sometimes I saw people hiding in the bushes near the road at pick up points, hoping either I hadn’t seen them or wouldn’t turn them in. I was usually driving to work and just waved to give a drop of ease into their obvious exhaustion and fear.

My neighbor’s dog brought the skull of a human child home one day, and I knew she was a migrant who died in her crossing. I wondered about her family. Did they leave her body? Did they die with her? Did she become lost and then die?

Years later, I crossed paths with Jody and learned about the Migrant Quilt Project. I checked the years and the locations. There was an unknown female child on the roster near that time and in that place. I knew I had to tell her story and quilted my panel – a dog bringing a small skull home, mesquite and sunsets and desert beauty in the background, shocked human in the foreground.

I hope the image prompts the viewer to imagine not only the humanity of the people who lose their lives in crossing, but the fundamental respect for life inherent even in a dog. She wasn’t chewing the skull. She knew it was out of place and needed human attention. Sometimes I wish humans had as much respect and compassion as the dog.

Laurel Wilson

Holding each small square and knowing that it represented a human life was very moving. Here was a person, often I did not even know the name, who entered the desert in hope but died in that same desert, their hope destroyed. I added images of cactus, particularly flowering ones, to restore a bit of their dream of a better life, one filled with beauty and peace. And I prayed for them and their families, some of whom may still be waiting to know what happened to them.

Reverend Bobbi Wells Hargleroad

When I pack for a trip, I am careful to consider what items I might need. When sewing the quilt I pondered the thought that migrants gave to the garments they brought on this important and dangerous journey. Much of the clothing was selected to protect the body from the harsh conditions they knew they would face – heavy denim to guard against thorns, dark clothing to avoid being seen. But there are also sentimental items – embroidered handkerchiefs and pieces of cloth with a connection to a loved one that might summon some protection for the soul. These migrants carried tangible mementos of cloth and thread in order to remain tied to the communities they might never see again. For me, the power of the quilt lies in part with our human instinct to do the very same thing – to hold onto tangible reminders of what we have lost – to make sacred what connects.

Diana Rix