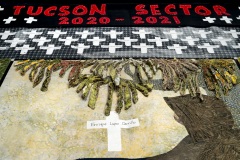

Quiltmakers’ statement:

Our Backyard Graveyard

What an honor and great responsibility is was to make this quilt. How could I help people who examine this quilt to see the humanity and lived lives of the people represented here who died in our desert? How could I make it more visceral and less cerebral? How could I honor their lives and bear witness to their deaths with dignity and respect? I wanted the quilt to say to the viewer, “Except for the accident of your birth, this could have been you.”

These were some of the ideas I pondered after learning I would make this quilt. Then I received the clothing that the migrants had worn. I spent quite some time simply touching and exploring the clothing. Then I started to pay attention to as many different familiar details in the clothing as I could, and that is what guided me. I imagined that I had picked out the various pieces of clothing – or that they had somehow been gifted to me. I noticed the beautiful embroidery that decorated the sleeve of a shirt and imagined myself looking at such a design on my own clothing during my day and having it give me pleasure. I noticed the patch of membership to an organization sewn onto a shirt and thought of groups that I had belonged to and proudly displayed on my own clothing. I noticed the tags in the clothing indicating its manufacturer, its size, what it was made of and how to care for it. And then, one day, it was as if these were my own clothes.

I pictured myself putting my own arm into the sleeve of a top, snapping or buttoning a cuff in place around my wrist. I imagined pulling on a pair of jeans, zipping the zipper, and putting something important into my pockets. I visualized choosing a hat to protect my face from the sun and wrapping food in a manta for the journey. Suddenly, it was very personal. I wrote Desconocido/a (unknown) on a cross and stitched the cross through the clothing and onto the background desert-colored fabric. I wanted the section of clothing to be able to hang loose from the background of the quilt so that one could appreciate the owner’s interaction with that piece of clothing. I used a crisscross embroidery stitch to help adhere the clothing to the background, to represent everything that is naturally sharp and harmful in the desert that would assault the clothes and body on the dangerous journey.

The centerpiece image of the quilt is of a person who had died sitting under the shade of a mesquite tree. It was designed by my friend Michelina Nicotera-Taxiera. Around this centerpiece I included the names on the crosses of the 95 people identified as dying in our desert. Beyond this central image are the 130 crosses of people who died nameless in the desert.

As I sewed on the crosses and presented each name to God, I was suddenly aware of reading Maria’s name. My mom’s middle name was Marie. Another name I read was Rogelino. My dad’s name was Roger. As I sewed, through my tears I imaged that Maria and Rogelino were my parents. My parents loved me and my brother so much that if we were living in danger or poverty, they would have decided to leave to find a place of safety for us. And then realizing that they died in the desert, I understood Rogelino and Maria’s sacrifice of love and hope.

As you examine this quilt, imagine that you are one of the people here – or that you know one of them. Make it personal. Maybe you were with them when they purchased that pair of jeans. Maybe you gave that shirt as a present to the person. Maybe you have a picture of the person wearing that hat in your photo album. How will we put an end to this graveyard growing in our backyard? The danger of the desert isn’t a big enough deterrence when your life is at stake. They are us, and we are them. How big are we willing to let this graveyard become?

Gale Hall